Talk delivered January 27, 2010 at the University of British Columbia, conference hosted by the Social Justice Centre, ‘Rethinking the Olympics’.

*

“The law is applied differently in the Downtown Eastside.” -Douglas King (Pivot Legal Society)[i]

In the context of a dual intensification of policing and local real-estate gentrification, a concentrated state of emergency or ‘state of exception’ has been applied to the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver. Today I want to use the concept of the ‘state of exception’ in the way it has emerged in aspects of 20th century juridical and political theory, surrounding in particular a triangle of figures – Carl Schmitt, Walter Benjamin, Giorgio Agamben. The first two are from the early part of the century, one a revolutionary and one a reactionary, while Agamben is our contemporary, writing in the emancipatory tradition of Benjamin.

The theory of the state of exception emphasizes the construction of a legal framework that subjects humans to the practice of a sovereign or statist gap. This gap is an exceptional space in which the sovereign state is placed outside or beyond the law. The exception is paradoxical because it refers not to a general lawlessness but rather to a space without law constructed within the application of the law itself. It is in this sense that the exception occurs not in spite of the law but as one of its supports as a precondition to the law’s application. As a consequence of the exception, human beings are found reduced to a “bare” existence, marginalized and stripped of dignity in the face of the law. The exception is twofold, because the state inflicts the exception on its subjects. Both are made symmetrically exceptional: the state is above and the subjects are below the law.

Thus there are three theoretical points to follow, which so far are merely claims: 1) there is an exception within the law that is necessary for the application of the law itself, 2) there is a position beyond the law, occupied by the sovereign authority of the state, 3) there are human subjects placed in the space of the exception, reduced to bare life and stripped of dignity.

As an initial example, I would like to talk about a recent law passed in the province of British Columbia: the Assistance to Shelter Act. This Act, recently passed by the British Columbia legislature, would seem to be a strange starting point in light of the fact that it remains unapplied to date. It rests at the level of a threat, whereas other concrete forms of policing have already been at work on the lives of the poor. I propose, however, that practices already in place to criminalize poverty in the city of Vancouver – which include a raft of police strategies surrounding the Safe Streets Act and Project Civil City (see Appendix, below) – can be best understood by reading backwards from the Assistance to Shelter Act. There have been recent assurance by the Vancouver police to not enforce the Act. Far from making the Act irrelevant, I will try to show that it is precisely this indeterminacy – an exceptional decision by the police in spite of the exact word of law – that underpins the state of exception itself. A cornerstone of the state of exception is the gap between the law and its implementation or suspension; between legislation and enforcement.

There is a space that separates the abstraction of the code, on the one hand, and the particularities of the situation, on the other. The upshot of this is that the use of police force in the name of a law must always exceed, in the particularity of its implementation, the generality of that law. A law must be sutured to its condition, bringing the gap into effect. What fills the space of the gap is a form of practice Giorgio Agamben terms ‘pure violence.’ ‘Pure violence,’ following Benjamin, denotes less the fact of raw force commonly understood by the term violence, although it encompasses that. Rather, ‘pure’ denotes a form of suspended practice that does not have the law as its immediate end. It places sovereignty outside the law, since the law sets in motion the suspended decision of the sovereign police, a decision necessary for the successful crossing of the legal zone of indeterminacy between the code and its effectuation.[ii] What is at stake in this process is a state that represents both the embodiment of the law and the embodiment of what is beyond it.[iii]

Homo Sacer

Out of exceptional process are created exceptional subjects, legally symmetrical. Like the state that rules them, exceptional subjects stand outside the law proper. Agamben terms these subjects homo sacer, borrowed from a category of Roman law designating those who are sacred, partly as a result of their transcendence of the law, yet whose lives can be destroyed or sacrificed with impunity.

Who is homo sacer? Or rather we could ask: From what legal structures do homo sacer emerge? For a moment, consider the Assistance to Shelter Act with an eye on its ‘state of emergency’ (and I remind you that the Act is specific to “extreme weather emergencies”). The Act, passed just in time for the Olympics, gives police the right clean the streets by using force against the will of anyone perceived to be homeless during a weather emergency, regardless of whether or not they have committed a chargeable offense. What exactly qualifies as “extreme weather conditions”?: “Temperatures near zero with rainfall that makes it difficult to remain dry, and/or sleet, freezing rain; and/or snow accumulation; and/or sustained high winds.”[iv]

With the Safe Streets Act and Project Civil City, we had a legal situation in which general rules were established.[v] Importantly, the rules themselves did not give specific criteria. These laws did not say, “target the poor of the DTES,” for example. Rather, as codes, they are neutral. Yet they work out their logic in specific ways. Like any other, their rules require the exceptional practice of the police. It is at the level of this exceptional practice that we find the most violence. In the case of Project Civil City and the Safe Streets Act, the rules resulted (and continue to result in) the targeted criminalization of the poor because of the exceptional practices of the police. The same applies for the Assistance to Shelter Act, which makes explicit what was latent in the Safe Streets Act and Project Civil City. However, what is significant is that the Assistance to Shelter Act goes a step beyond them both, since the code of the Act is itself inscribed as exceptional. There is a double exceptionality. First, there is the gap between the law and its effectuation. Secondly, this gap is re-inscribed into the formal codes themselves. This takes place to the extreme extent that, for example, the Assistance to Shelter becomes both a law and not a law. I will quote Minister Rich Coleman, responsible for the Assistance to Shelter Act:

“This will be a piece of legislation. It will be a law.”[vi]

“I’ll repeat myself. They’re [the police] not enforcing a law or an offence but providing assistance.”[vii]

As Benjamin showed, the exception has paradoxically become the rule.[viii] Schmitt himself, the great opponent of Benjamin, writes in this precise sense of the inscription of “general indeterminate clauses” into the law, often surrounding the usage of such ambiguous early century legal concepts as “good morals,” “proper security and order,” “state of danger,” etc. What occurs is that with the support of indeterminate clauses, the exception is itself legislated into being, securing the exception as literally a state of exception.

It is precisely out of this juridical order that human lives are reduced to a bare legal function, animalized and effectively subjected to the arbitrary advances of armed authority. I have given examples, and there are countless more: the routine discarding of people’s personal possessions by the City’s engineering department; cycles of perpetual imprisonment that grow from offenses as minor as jaywalking; police beatings and daily harassment.

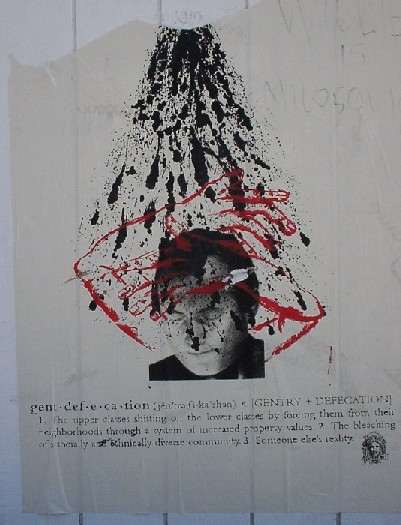

Gentrification

The practices just listed are what sustain the class divisions in the context of gentrification, the true topic of concern for residents of the Downtown Eastside. Gentrification is a process that includes not only heightened police activity, but also increased private security and surveillance in the community, self-segregated exclusive gentrifier areas, and widespread poor-bashing. In the last year, gentrifiers have thrown bricks, bags of shit, and whole television sets at residents of the Downtown Eastside, and of course they have gone unpunished. The gaps in the law are filled by class interest, which is obvious enough, but what needs to be stressed is that these ad hoc forms of gentrification – rents and bags of shit – cannot succeed without a legal framework for the state of exception. It has to be understood that gentrification is a common form of class domination, but also a particular unique form requiring particular forms of violence. It asks the state to perform a kind of human displacement that evictions and real-estate markets alone cannot carry out. Gentrification displacement – the clearing out of our neighborhoods for the settlement of the middle classes – requires the creation of the legal category of homo sacer, the subject reduced to bare life and stripped of human dignity, criminalized for being poor with no standing.

Conclusion (Concluding remarks)

While I have depicted aspects of the concreteness of the situation, I would also say that I’ve presented a problem for activism: the question of how we are to engage in the class struggle and side with the poor. Do we entangle ourselves in the legal triangle of sovereign-police-subject? I have suggested that in a class society, the gaps in the law – the spaces of exception – are occupied by dominant interests. The challenge should not be to bring the law ever closer to the police, as the dream would appear in liberal aspirations for a legal narrowing, however noble those dreams are. Rather, in the context of the heightened policing and criminalization of the poor, we must work on solutions that in themselves exceed the logics of sovereignty, law and police. For the people who live in the neighborhood this is almost too obvious to mention. The community says it everyday, if we are willing to listen: the truest solutions will have no relation to the logic of Policing.

Nate Crompton

I would like to acknowledge my debt to Bahram Norouzi, especially an unpublished work from 2009 by Bahram and Stef Ratjen entitled, “A City for Animals: Agamben’s State of Exception, quangos and the 2010 Olympics”.

[i] ‘Judge raps Vancouver police tactics’ CBC February 18, 2010 http://www.cbc.ca/canada/british-columbia/story/2010/02/17/bc-legal-rights-downtown-eastside.html

[ii] Schmitt’s famous definition of the sovereign reads simply, “he who decides on the exception.” Carl Schmitt, Political Theology (Chicago: MIT Press, 1988) p. 5

[iii] I would like to give a stark illustration. Thanks to the tireless work of advocates and a few journalists, the police have been for the past twelve months asked repeatedly if they would be willing to give a public promise not to use agents provocateurs during the Vancouver Olympic Games. After these painful months, the police have given a certain assurance not to use agents provocateurs. However, they retain the right to take over and direct activist groups from within, as well as the right to commit illegal acts once inside these groups. see, ‘Police reserve the right to take over activist groups for 2010’ BC Civil Liberties Association, December 22, 2009 http://www.bccla.org/pressreleases/0912ISU.html

[iv] Minister Rich Coleman, Third Reading of parliamentary Bill 18, ‘Assistance to Shelter Act’, Page 2434: http://www.leg.bc.ca/hansard/39th1st/h91117p.htm

[v] see Appendix: Legislation Timeline

[vi] Minister Rich Coleman, Third Reading of parliamentary Bill 18, ‘Assistance to Shelter Act’, Page 2449: http://www.leg.bc.ca/hansard/39th1st/h91117p.htm

[vii] Minister Rich Coleman, Third Reading of parliamentary Bill 18, ‘Assistance to Shelter Act’, Page 2448: http://www.leg.bc.ca/hansard/39th1st/h91117p.htm

[viii] “The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the “emergency situation” in which we live is the rule.” Walter Benjamin, Theses on the Philosophy of History (1939) http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/benjamin/1940/history.htm

_________________________________

APPENDIX: Legislation Timeline

2005: Safe Streets Act

-changes in the Trespass Act, targeted to the practices of the poor

-restrictions on panhandling

-spearheaded by the DVBIA, with the aim of, “making Downtown Vancouver North America’s number one business-friendly downtown core.”

2006: Mayor Sam Sullivan’s reports to council on “public disorder” lead to Project Civil City

-how can we keep the class gap wide without having poor people decrease the property values of the downtown core

-VPD votes unanimously to endorse Project Civil City, adopting quotas and a “results-based” commitment to the project. 20% increase in charges falling under the Safe Streets Act between 2007 and 2008 (see 2008 Annual Business Plan, VPD)

2007: the City approves more money for Project Civil City.

–MTI (Municipal Ticket Information) project give police the ability bypass court processes in issuing tickets: spitting and defacating, $100; dog off leash or no dog license, $250; objectionable noise, $150; jaywalking, $100